Safety in Numbers

Brighter Planet's blog

Striving for a great API client

I wanted to take a moment to share some of the principles and technologies we used to build client libraries for our CM1 web service. As developers, we know how frustrating it can be to learn a new API and we keep that in mind as we design our client libraries to spare others of the same frustration.

Make the API client simple

Give first-time developers early wins by avoiding signups. Don’t waste developers’ time with weird object instantiation patterns. A good API is one that takes very little configuration and setup. If I want to run a query, I want to do it with as few lines of code as possible. With our carbon gem you can be up and running with a single function call:

result = Carbon.query('Flight', {

:origin_airport => 'MSN',

:destination_airport => 'ORD'

})

puts "Carbon for my cross country flight: #{result.carbon}"No account setup is needed until you’re in production. Once you’re ready, you can sign up for an API key and set it:

Carbon.key = 'MyKeyABC'Our JavaScript client works similarly:

var CM1 = require('cm1');

CM1.impacts('flight', {

origin_airport: 'IAD',

destination_airport: 'PDX'

},

function(err, impacts) {

console.log('Carbon for my cross-country flight: ',

impacts.carbon);

});Another benefit of a simple API is that it’s easier to mock out when testing an application against it.

Craft well-written documentation

Document your client library’s code, README, and website. Never assume a new user is familiar with all of the terminology your API uses and explain it well. Note that the simpler your API is, the easier it’ll be to write documentation.

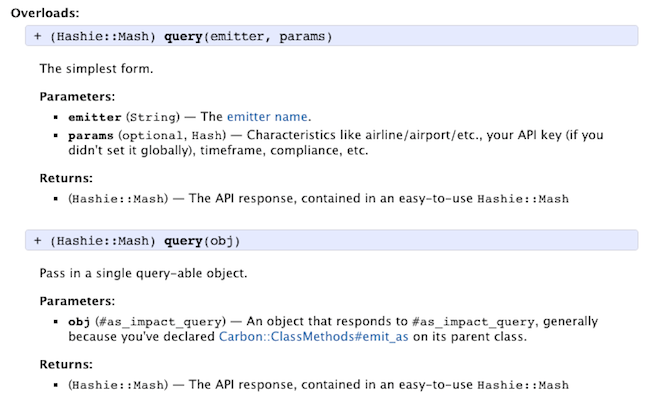

Ruby docs with YARDoc

You may be familiar with Ruby’s RDoc documentation generator. YARDoc is similar, but adds some handy directives that better format your documentation.

The @param directive - @param [<type>] <name> <description> - defines a parameter that a function accepts.

The @return directive - @return [<type>] - specifies the return value of the function.

Each @overload directive @overload <function>(<param>) tells YARDoc that the function can be called with different method signatures.

Here’s an example from the carbon gem:

# @overload query(emitter, params)

# The simplest form.

# @param [String] emitter The {http://impact.brighterplanet.com/emitters.json emitter name}.

# @param [optional, Hash] params Characteristics like airline/airport/etc., your API key (if you didn't set it globally), timeframe, compliance, etc.

# @return [Hashie::Mash] The API response, contained in an easy-to-use +Hashie::Mash+

#

# @overload query(obj)

# Pass in a single query-able object.

# @param [#as_impact_query] obj An object that responds to +#as_impact_query+, generally because you've declared {Carbon::ClassMethods#emit_as} on its parent class.

# @return [Hashie::Mash] The API response, contained in an easy-to-use +Hashie::Mash+

def Carbon.query(*params)And here’s the YARDoc output:

These directives are important for dynamically typed languages like Ruby.

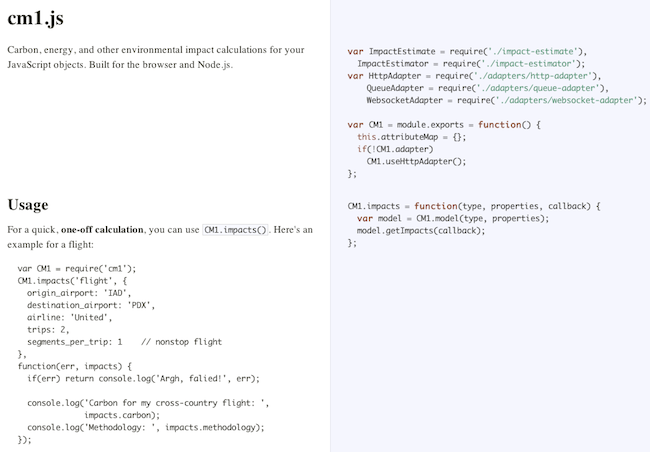

Docco

Docco provides “narrative” style documentation that reads more like a manual than your typical API reference. It turns your comments into documentation on one side of the page, with the actual code on the other side. CM1.js uses Docco to great effect.

HTML

Having a dedicated web page for your client or API can be a big help. For example, our CM1 site, rather than being a brochure for our service, is a guide to using our API and an introduction to our language-specific API clients.

Eat your own dog food

It should go without saying, but by using your API for your own projects, you instantly become a constructive critic of your own work. The great benefit is that because you own the API, you get to change it if you don’t like it! This is particularly useful in early stages of API development.

Use VCR or other HTTP mocking libraries

VCR is a great testing tool that fakes out HTTP requests so that your tests run quickly and are run against real responses. A nice feature of VCR is that you can configure it to refresh response data, say, every month so you can verify that your client still works with your latest API.

Here’s an example from the carbon gem:

describe Carbon do

describe '.query' do

it "calculates flight impact" do

VCR.use_cassette 'LAX->SFO flight', :record => :once do

result = Carbon.query('Flight', {

:origin_airport => 'LAX', :destination_airport => 'SFO'

})

result.decisions.carbon.object.value.should be_within(50).of(200)

end

end

end

endIn JavaScript land, a tool called replay provides similar functionality.

Do the multithreading for them

It’s best to save developers the trouble of handling performance issues by providing a solution. This goes hand-in-hand with eating your own dog food. We took our own pattern of parallelizing CM1 requests and baked it into the carbon gem. Simply pass Carbon.query an array of calculations to perform, and we’ll use the amazing Celluloid gem to parallelize the requests. Celluloid provides a pool of threaded workers for this task.

The carbon gem first creates a Celluloid worker pool:

require 'celluloid'

module Carbon

class QueryPool

include Celluloid

def perform(query)

query.result

end

end

endThen it hands out each query to workers in the pool:

queries.each do |query|

pool.perform! query

endThis is a super-simple way to provide parallelism to your API users.

Make it asynchronous

An interesting trend among API providers has been the idea of providing a queued interface. This makes asynchronous processing much easier for developers and also takes some load off of your web servers. We even played around with an SQS-based client at one time with our carbon gem. In the future, we could see a Socket.IO-based, asynchronous API for our JavaScript client.

What blog is this?

Safety in Numbers is Brighter Planet's blog about climate science, Ruby, Rails, data, transparency, and, well, us.

Who's behind this?

We're Brighter Planet, the world's leading computational sustainability platform.