Safety in Numbers

Brighter Planet's blog

Virtual servers, real impact

Last week we announced Tronprint, our Ruby library for measuring an application’s carbon footprint in real time. There’s a subtlety to the way that my colleague Derek designed Tronprint that didn’t hit me for a while: as a piece of monitoring software it’s “inside-out” rather than “outside-in.” It’s a simple distinction that’s going to let us continue to address sustainability in this new era of cloud computing.

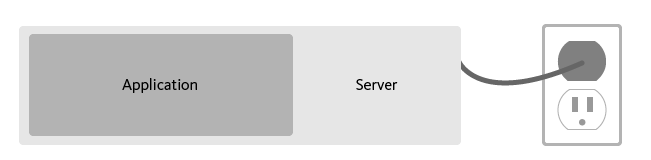

First, let’s look at an old-school web application:

{.wide}

{.wide}

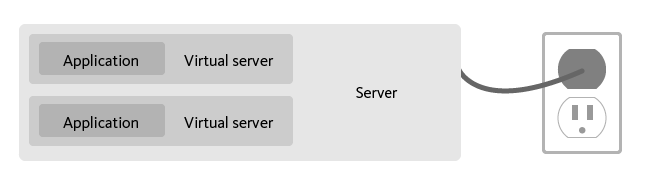

Calculating the application’s footprint in this case is pretty easy—just base your calculation on the electricity used by the server. Unfortunately this infrastructural design is rarely ever seen in the wild anymore. Virtualization presents one challenge:

{.wide}

{.wide}

How do you allocate impact among virtual servers? If you control the hypervisor (the coordinating software on the physical host server), presumably you would have access to some data that would help determine this. But oftentimes owners of virtual servers do not have access to this data.

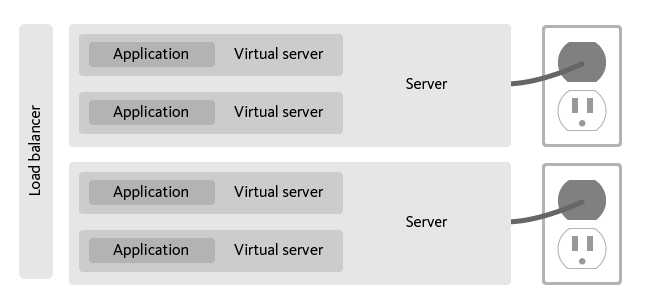

Let’s take this a step further and add load balancing:

{.wide}

{.wide}

Modern load-balanced architectures can have an arbitrary number of “instances” of the application running on an arbitrary number of virtual machines. At this point you can see our analysis breaking down: the physicality of these computations is both mysterious and irrelevant.

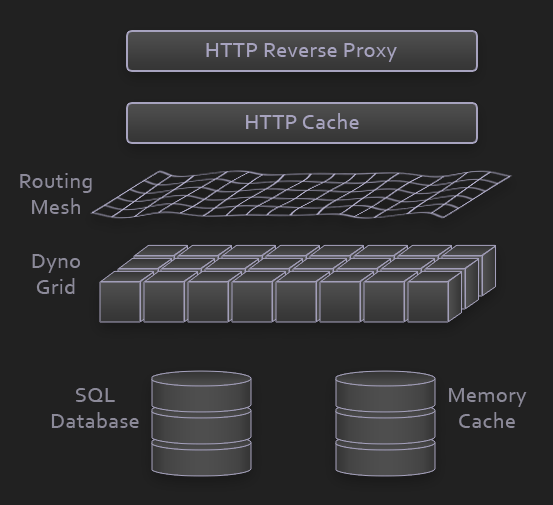

The abstraction of physical resources reaches a kind of apotheosis with Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS) offerings like Heroku:

Routing mesh? Dyno grids? When Seamus, Robbie, and I were having lunch with the Heroku folks last week, they emphasized that they’re trying to keep the Heroku experience entirely free of the notion of physical servers.

This is a good thing. But as our applications grow ever more distant from the silicon they run on, it’s easy to lose sight of the fact that those circuits are electrical circuits—the server may be virtual, but the impact’s very real.

So, as the operator of an application that lives inside of a grid inside of a mesh inside of a platform inside of a virtualized datacenter, how are you to know your application’s footprint? Having done everything they can to keep you from the physical, are your service providers unwittingly hamstringing your sustainability agenda?

The answer to this question, it turns out, is the simple distinction that sets Tronprint apart: monitor your application’s resource use from the inside out. In a supervirtualized architecture, after all, the only thing you have any truly predictable control over is the application itself.

I like to imagine Tronprint as being a born-and-bred native resident of the cloud. There are dozens of layers of technology keeping the cloud alive: servers, routers, load balancers, datacenters. But just as we don’t need advanced knowledge of astrophysics to carry on our daily lives here on our planet, Tronprint doesn’t care about all that. It lives on the surface, among the applications, helping them out.

Subtle, right? I wonder if Derek knew just how clever he’d been :)

What blog is this?

Safety in Numbers is Brighter Planet's blog about climate science, Ruby, Rails, data, transparency, and, well, us.

Who's behind this?

We're Brighter Planet, the world's leading computational sustainability platform.